All chatbots are not created equal.

No, that isn’t the opening line of a dystopian science fiction novel (yet). Instead, it describes what the chatbot landscape looks like right now.

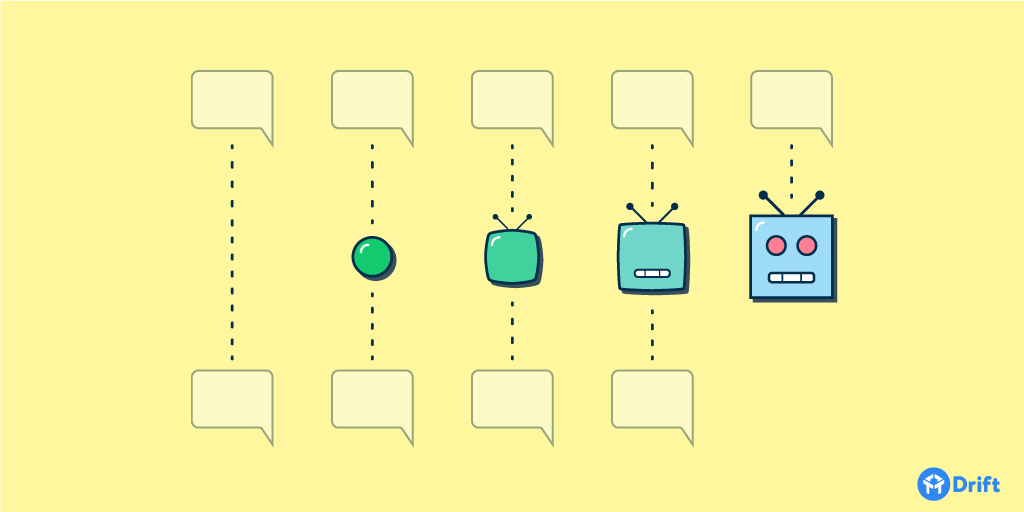

We often think about chatbots as a single category that has universally shared goals (e.g. to beat the Turing test — to become indistinguishable from humans during conversation). But in reality, today’s chatbots fall along a spectrum.

At one end of the spectrum are chatbots that are designed to replace human-to-human communication.

At the other end of the spectrum are chatbots that are designed to facilitate it. And all along that spectrum you’ll find chatbots that can engage with you in a variety of ways and to varying degrees.

Drift product manager Matt Bilotti explained it to me like this:

All the way on the right you have totally programmatic chatbots, where you give them specific prompts, or ask them specific questions, and they give you specific responses. Everything is built in. It’s a strictly human-to-chatbot conversation.

Move over a bit and you have chatbots that try to extract as much information from you as possible on their own, but can ultimately fall back on a human if it’s absolutely necessary.

It’s like when you call a customer support line and get that pre-recorded voice that asks, “What is the nature of your call, this, this, or this?” and then you respond and get another set of questions, and another, and another. But eventually, if you’re persistent (or you repeatedly mash the “0” key with your thumb), you can reach a human.

Cross the halfway point and you get to where our chatbot software fits into the picture. While the chatbots on the right side of the spectrum were focused on replacing or minimizing human-to-human interaction, the chatbots on the left side are geared toward enhancing it.

Driftbot, for example, acts sort of like an intelligent switchboard for live chat. It asks you questions not so it can attempt to resolve your issue on its own, but so it can figure out who the best human is for you to talk to. Then it connects you to that human as quickly as possible.

Move over even further and you’ll find Driftbot’s predecessor: a super-minimal chatbot that would ask people a single question before connecting them with a human (“Hey, just in case we get disconnected, what’s your email address?”).

Finally, if you strip away that super-minimal layer of chatbot interaction you’re left with no chatbot interaction at all — You’re chatting human-to-human.

How we decided what type of chatbot to build

No position on the chatbot spectrum is inherently better than another. Ultimately, where a chatbot falls along the spectrum should depend on its particular purpose.

For example, it makes sense that the weather forecasting chatbot Poncho for Facebook Messenger is all the way over on the no-human/chatbot-only end of the spectrum. That’s because Poncho’s purpose is to programmatically respond to specific questions. There’s a defined set of things users can expect the chatbot to be able to tell them. So if a user goes off-script and Poncho gets stumped, it doesn’t necessarily ruin the experience when that conversation comes to an end.

With Driftbot, on the other hand, our goal was to prevent conversations from coming to an end. That first iteration of the bot, where we asked for an email address, was intended to minimize missed connections. But ultimately it didn’t help with the other goals we were working toward (like better-qualifying the chats that were coming in). It also felt impersonal, because it was context-irrelevant — it would say the same thing to everyone.

Looking for some inspiration? Check out our top chatbot examples.

Our solution was to move a little bit closer to the chatbot-only end of the spectrum. We needed something that could dig a little deeper, engage a little further. But at the same time, we were weary of going too far into chatbot-only territory.

So we landed somewhere in the middle of the spectrum. Driftbot will engage with you to a point, but if the conversation gets off-track, the chatbot defaults to connecting you to a human.

For example, if you go to the Drift website and start a live chat, Driftbot will ask you: “Hey! Would you like to talk to sales, support, or anyone?” If you ignore those three options presented to you and instead respond with something like, “I’m looking for answers to my questions,” Driftbot won’t try to figure out what those questions are — it will simply connect you to someone.

In the future, we might move a bit further toward the chatbot-only end of the spectrum and start using to Driftbot to ask people what their questions and issues are before connecting them with a human (provided that ends up helping people get answers more quickly).

What we don’t ever want is to completely replace human-to-human conversations, or see someone end up in an endless cycle of nonsensical chatbot talk. (Did someone say SmarterChild?)

While those types of chatbots have their place, from a technology standpoint they’re not yet able to compete with humans when it comes to providing customer support and having conversations about your business.

Final thought: keeping it human

In 1950, Alan Turing proposed his famed test, which (simply put) set the precedent that a truly intelligent machine should be able to talk to a human without the human knowing it’s a machine. By 1966, we had ELIZA — a computer program that could mimic the responses of a psychiatrist and, for short spurts, carry on convincingly human conversations.

Those conversations were so convincing, in fact, that at least one person who worked at the MIT lab where ELIZA was being built would request to have time alone with it so they could speak in private.

While ELIZA couldn’t beat the Turing test, flash forward to 2014 and we have a stronger contender: At the Turing Test 2014 Competition at the Royal Society in London, the Eugene Goostman chatbot was able to convince 33% of judges that it was actually a 13-year-old Ukrainian boy.

Yes, these types of chabots are pretty amazing … if not a little creepy. But it’s important to realize that, today, these human-substitute chatbots represent just one extreme of the chatbot spectrum.

At Drift, we don’t want our chatbot to trick you into thinking that it’s a human. We want it to provide you with a great experience, but we also want you to know that it’s a bot.

When customers get Driftbot set up on their sites, they’re able to name it and create an avatar for it. And while theoretically you could give Driftbot your name, and put your picture as the avatar to make it appear as though the chatbot is actually you, we strongly recommend against doing so.

Imagine the frustration you’d feel if you started talking to what you thought was a human only to find out it was actually a bot. It’s a bad experience.

As Matt told me, “It’s important to set the context that it’s not human, because it helps keep the world of bots honest and transparent, and helps set the right expectations for the interactions you’re going to have.”