“Old cars go to scrapyards. Old Porsches go to museums.”

That’s a brilliant bit of advertising copy used by Porsche, a brand that’s become synonymous with the revving of high-performance engines and sleek sports cars racing down tracks at speeds north of 200 mph.

But here’s the thing:

If you go to the actual Porsche museum in Stuttgart, Germany to see the old Porsches, you might be surprised to discover that the world’s first Porsche wasn’t powered by a V6, or a V8 — heck, it didn’t rely on an internal combustion engine at all.

The world’s first Porsche was electric.

Hand-built by Ferdinand Porsche in 1898, the “P1” relied on a three-horsepower electric motor and could cruise around at speeds of about 20 mph for between three and six hours (before running out of juice).

While it wasn’t a “high performance” vehicle by any stretch of the imagination, the P1 was perfectly suited for driving around town and going on short trips.

And that was back in 1898.

This got me thinking: Why are electric cars only starting to catch on now, when the underlying technology has been around for more than a century?

And what are some other popular technologies that have been rediscovered in recent years?

First things first: I’ll explain how we went from the P1 to the Tesla Model 3. Then I’ll talk about two other popular technologies — virtual reality and messaging — that were also developed decades before they became widely adopted.

1) The Electric Car

So it turns out Ferdinand Porsche’s P1 wasn’t even close to being the first electric car.

Scottish inventor Robert Anderson has a strong claim to that title, having built a crude electric carriage — powered by non-rechargeable batteries — back in the 1830s.

Then there’s the American inventor Thomas Davenport, who built an electric motor in 1834 and then used it to power a small train in 1835. Davenport’s train is often considered to be the first practical electric vehicle.

Over the next several decades, the invention of the lead-acid battery (and subsequent improvements to the battery’s storage capacity) would give rise to the rechargeable electric car we’re familiar with today.

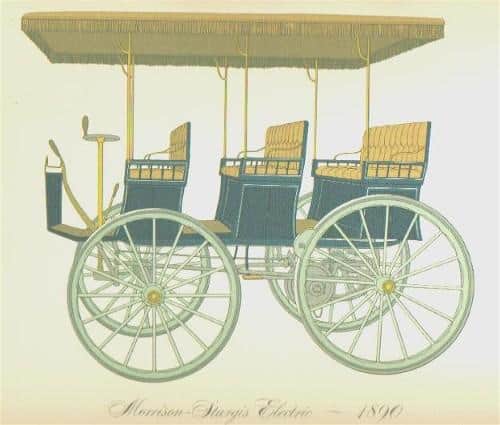

For example, in 1890, William Morrison of Iowa debuted his Morrison Electric. Powered by 24 battery cells, each of which weighed 32 pounds, the Morrison Electric could achieve a range of about 100 miles on a single charge.

(image source: American Automobiles)

By 1900, 28% of the cars being manufactured in the U.S. were electric.

And during that same time, approximately 1/3 of all the cars in Boston, Chicago, and New York were electric.

Sooo what the heck happened?

Why did electric cars fall off the map for an entire century?

There’s no single answer, but historians agree that the debut of the gasoline-powered Ford Model T in 1908 definitely helped seal the electric car’s fate (at least temporarily).

While electric cars were quieter, easier to driver, and, of course, easier on the ole lungs in comparison to their gas-guzzling counterparts, the Ford Model T had one major advantage.

It was inexpensive.

In 1912, a gasoline-powered Model T sold for around $650. A comparable electric car, meanwhile, sold for around $1,750.

In the decades to follow, consumer interest in electric cars would flatline, and gasoline would become the preferred fuel of the American automobile.

The Rediscovery

The argument could be made that Ford killed the electric car. But flash forward to today, and oh how the tables have turned.

On April 3, 2017, the electric car manufacturer Tesla surpassed Ford in market value to become the second most valuable car company in the country.

Then on April 4, 2017, Tesla surpassed GM to become the most valuable car company in the country.

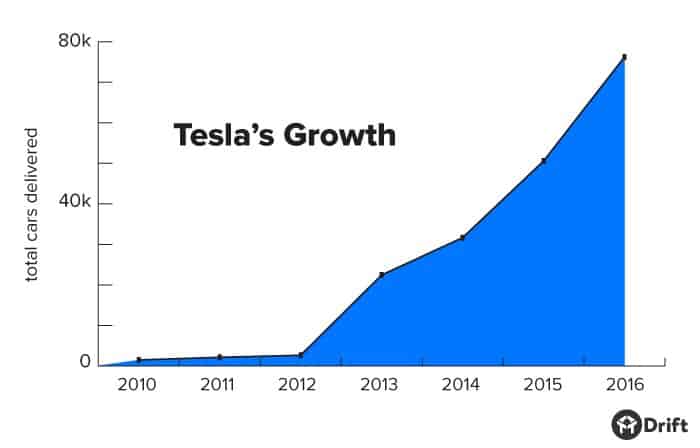

Tesla has gone from delivering 1,500 electric cars to customers in 2010, to delivering 76,230 electric cars to customers in 2016.

The Electric Vehicle Transportation Center predicts that by the year 2024, 740,000 electric vehicles overall will be sold annually, and the total number of electric cars on the road will reach 4 million.

And although we’ve really only started to feel its effects in the past few years, we can trace this resurgence in interest in the electric car back to the 1970s, when surging oil prices left the world wondering how life could go on if people could no longer fill up their tanks at the pump.

By the 1990s, increased interest in environmentalism meant that more and more consumers were becoming conscious of their carbon footprints.

Suddenly, the conditions were just right for the electric car to make its comeback. And Elon Musk and his Tesla co-founders jumped on the opportunity.

Perfect timing.

2) Virtual Reality Headsets

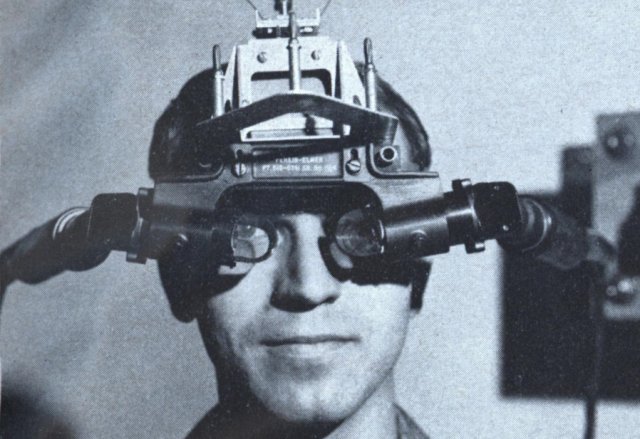

(image source: Ars Technica)

People have been strapping strange electronic contraptions to their faces with the hopes of experiencing virtual reality for a lot longer than you might imagine.

True, the term “virtual reality” didn’t become popularized until 1987, but as early as the 1960s engineers were building head-mounted displays (HMDs) that were capable of motion tracking (i.e. where the image/video being displayed responds to a user’s movements).

From the Headsight, developed by two Philco Corporation engineers in 1961, to the Sword of Damocles, developed by the “father of computer graphics” Ivan Sutherland in 1968, dozens of HMDs were developed in those early years — but none of them took off commercially.

There really just wasn’t a market for them.

Then came the rise of home video game consoles. Atari in the 1970s. Nintendo and Sega in the 1980s. Playstation in the 1990s. And with them came a renewed interest in virtual reality.

In 1995, Nintendo released Virtual Boy, a table-top video game console that could display games in stereoscopic 3D.

Then in 1996, Sony entered the virtual reality field with their Glasstron headset, which was designed to create an immersive gaming experience, complete with audio.

At the time, it might have felt like virtual reality headsets were about to take off.

But ultimately, the timing wasn’t right.

For many people, the technology felt too anti-social. And it just didn’t succeed in enhancing the gaming experience.

As a result, consumer interest waned.

Nintendo discontinued its Virtual Boy in 1996 (a year after its introduction), while Sony stopped producing its Glasstron in 1998.

The Rediscovery

In 2011, 18-year-old Palmer Luckey built a rough prototype of a virtual reality headset in his parents’ garage.

Like its predecessors, Luckey’s headset could display games in stereoscopic 3D, and it had built-in audio for creating a more immersive experience.

In 2012, Luckey launched a Kickstarter campaign to fund the further development of his headset…

He raised $2.5 million.

Two years later, Facebook came knocking.

They were interested in Luckey’s headset — the Oculus Rift — and were willing to pay $2 billion for it.

Wait, what?

True, the Oculus Rift is technologically superior to Nintendo’s Virtual Boy and Sony’s Glasstron, but the underlying application is still the same: You’re still strapping something to your face and entering an isolated game-playing environment.

So, what’s changed?

While we’ve had virtual reality headsets for decades, we’ve only recently started to see the development of true virtual worlds — online universes where gamers can go to engage with other gamers.

Instead of being seen as anti-social and isolating, virtual reality headsets are now starting to be seen as a technology for connecting and communicating.

Another change: People now have the ability to create their own content for virtual reality headsets.

With Google’s Daydream platform, for example, you can use your phone to take a panoramic photo and simultaneously record audio, then you (or anyone) can experience that photo in three dimensions (and with sound) via the Google Daydream View headset.

These types of applications reinforce the idea of virtual reality being a tool for sharing and connecting, which was lacking in the previous iterations of the technology.

3) Messaging Apps

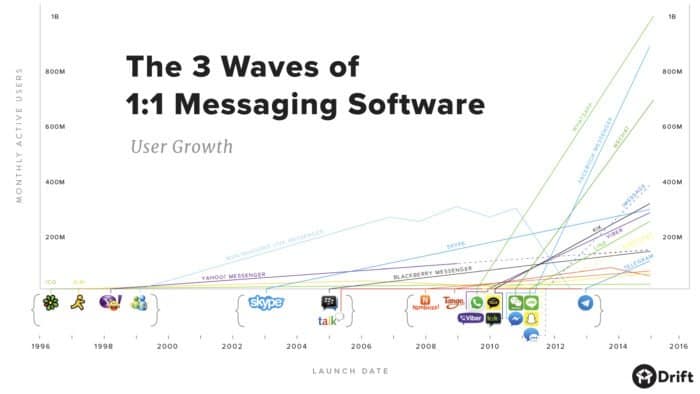

In the mid-1990s, the first wave of messaging software kicked off with ICQ in 1996 and AIM in 1997.

Then Yahoo! Messenger entered the scene in 1998, and MSN/Windows Live Messenger appeared a year later in 1999.

These early messaging applications gave us the same basic functionality we find in messaging apps today: one-to-one chat, plus the ability to chat in groups and set active/away statuses.

As was the case with those early electric cars and virtual reality headsets, these early messaging programs seemed destined for greatness … but the timing just wasn’t right.

The rise of cell phones and SMS text messaging would put instant messaging services like AIM at a major disadvantage. The underlying issue: Those early messaging services weren’t mobile — they were tied to desktops.

But in a few years, that all would change.

The Rediscovery

Today, billions of people around the world use messaging to communicate.

Whether it’s chatting with friends via Facebook Messenger (1.2 billion monthly active users), or chatting with coworkers via Slack (4 million+ daily active users), it’s clear that messaging has become an incredibly popular communication channel.

In fact, 3 out of 10 people around the world would give up using the phone altogether if they could using messaging instead.

So, why didn’t messaging see this type of adoption back in the mid-1990s?

One big reason: There weren’t smartphones back then.

By the early 2010s, the ubiquity of smartphones had made messaging apps a viable (and less expensive) mobile messaging alternative to SMS.

And as you can see in the chart below, usage rates in this latest wave of messaging completely dwarf the other waves of messaging that have come before it.

Ultimately, instant messaging apps like AIM didn’t fade away because their technology was subpar, they faded away because they were too early.

Final Thought: It’s All About Timing

In the tech world, timing is everything.

A few months too late bringing your idea to life, and you’ve missed your chance.

Show up too early, however, and you face an entirely different set of challenges.

So the key to success isn’t just building solid tech, it’s getting the timing right. And in order to do that, we have one suggestion:

To quote Drift CEO David Cancel:

So much of what we do comes down to timing. There’s nothing worse than being way too f’ing early. I attribute getting better at timing to one change: Focusing on the customer and not on my ideas. It’s really that simple. If we listen really closely to our customers they will tell us if our timing is right on, too late, or too early.