Sell me this pen.

It’s the best-known and most frequently dissected interview question that salespeople face, yet in most cases, it’s not even phrased as a question.

Here’s how it usually goes down: The interviewer will lean across the table (perhaps with a smirk, in anticipation of what’s to come).

Then she’ll slowly open her hand to reveal the object while simultaneously speaking those four famous words …

Sell me this pen.

Of course, the sales experts of the world will tell you that the pen problem is all about evaluating a candidate’s approach to selling.

A “correct” answer will demonstrate that the candidate knows how to tease out and identify the needs of the prospective customer, and is then able to express the value of the pen in terms the prospective customer will appreciate and understand.

And while this can be a useful exercise, it’s also an exercise that’s rooted in a very traditional approach to selling — an approach that puts the burden of proving a product’s value on the shoulders of a salesperson, as opposed to letting a prospective customer discover the product’s value on his or her own.

PS. Are you ready to generate leads for your business without forms? See why 50,000+ businesses choose Drift.

A Different Solution To The Pen Problem

If Slack co-founder and CEO Stewart Butterfield were faced with the pen problem — “Sell me this pen” — I’d like to think that his initial response would simply be, “No.”

But when pushed to elaborate, his explanation might go something like this:

Instead of me trying to push this pen on you, I’m going to create a better pen. Scratch that: I’m going to create the best pen. I’m going to do extensive user testing, make changes based on what I learn, then do more testing, then make more changes, and after I go through this cycle enough times, I’ll arrive at a product that is far superior to the pen currently sitting on your desk. And that’s when I’ll start selling you … on how amazing it is to take notes and sign signatures with pens.

Eventually, through word-of-mouth and some basic advertising, my brand will become synonymous with the art of writing with pens. Meanwhile, my superior pen product will have hit the market, and you’ll inevitably hear about how great it is from friends and coworkers. Then one day, you’ll try it. And you’ll love it.

And you’ll want one.

Alright, yes, I know this sounds like some fanciful bullshit.

And if you’re applying for a sales role, using such a response will certainly raise some eyebrows, but it probably (definitely) won’t help your chances of getting the job.

After all, you’d essentially be telling the interviewer that if the company had an amazing product, and an amazing brand, they wouldn’t need to be hiring for that sales role in the first place.

And while it may sound far-fetched or impractical to forgo using a traditional sales organization, and to instead depend solely on your product and your brand in order to grow … it’s not impossible. Companies have done it. And most recently, Slack did it.

Here’s the real story behind Slack’s explosive growth.

Explosive Slack Growth

Slack Technologies (originally Tiny Speck) launched a beta version of their messaging software in 2013.

In 2014, they launched officially with 16 thousand active users. By year’s end, Slack would have 285 thousand active users — 73 thousand of them paid.

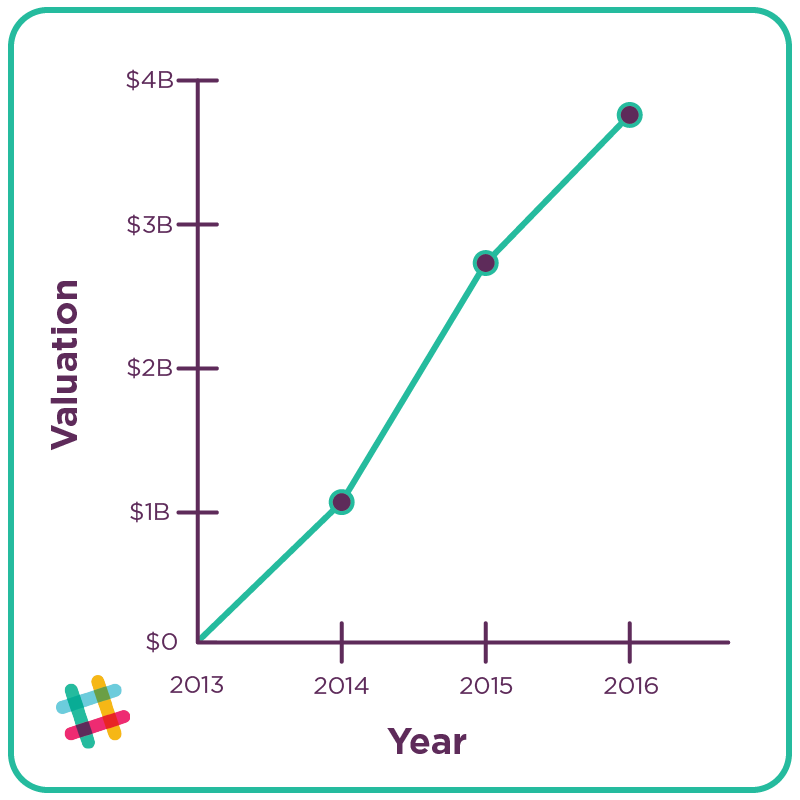

Oh, right, and Slack closed out 2014 with a $1.12 billion valuation (thanks to a $120 million round of funding led by Google Ventures and Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers).

In 2015, Slack broke the 1-million-active-user mark and ended the year with 300 thousand paid users. They also raised a $160 million round led by Social Capital, which put their valuation at $2.8 billion.

2016? Slack surpassed 2 million active users — 675 thousand of them paid — and they raised a $200 million venture round led by Thrive Capital that put their valuation at $3.8 billion.

To be sure, there’s no single factor that can account for Slack’s utterly, ridiculously, supernaturally high level of growth.

But we do know that during the first several years, Slack didn’t have an outbound sales team, nor did they have an elaborate marketing operation.

So cold-calling and lead generation/lead nurturing campaigns, the staples of many high-growth SaaS operations, weren’t levers they were pulling.

And yet, Slack was able to go from 0 to nearly $4 billion in less than four years.

How the heck did they do it?

An Experienced Founding Team

Butterfield co-founded Slack with Eric Costello, Cal Henderson, and Serguei Mourachov … all of whom were also instrumental in helping Butterfield build an earlier company: Flickr.

Launched in 2004, Flickr was the brainchild of Butterfield and wife Caterina Fake. But instead of setting out to revolutionize the world of online photo-sharing, the husband-and-wife developement duo came up with the product while building a massively multiplayer online game (MMO).

Part of the game — which was called Game Neverending, in case you were wondering — required the ability to upload and share photos. And after building that photo-sharing feature, Butterfield and Fake realized it was perhaps a more interesting product than the game itself.

In March of 2005, just a year after its launch, Flickr was acquired by Yahoo for an estimated $35 million, which is both an incredibly high sum (by my standards) and an incredibly low sum (by tech company exit standards).

If Butterfield and co. had held off selling Flickr for just a little bit longer, they likely would’ve seen a much larger return. At the time, the post-dot-com-bubble malaise was starting to lift, and tech companies were seeing an upswing in their valuations.

Just months after Flickr’s exit, in July of 2005, Myspace got acquired by News Corp. for $580 million. Then, in 2006, YouTube got scooped up by Google for $1.65 billion. (Suddenly, $35 million for what was at the time the world’s leading online photo-sharing service sounds like a ripoff.)

Looking back on the Yahoo deal in a 2014 interview with TechCrunch, Butterfield readily admits that it was a mistake to sell Flickr so early.

“We definitely made the wrong decision in retrospect. We would’ve made 10 times [what we did]. But it’s not like I regret it.”

Today, Butterfield’s new company, Slack, isn’t worth just 10 times what Flickr was sold for, it’s worth more than 100 times that figure.

Clearly, Butterfield and co. have learned from their past mistakes. But at the same time, they’ve also stuck to the same product-development playbook they used to come up with Flickr.

In a strange twist of fate, or irony, or however you want to characterize this situation, Slack started out as a feature in an MMO the team was developing (called Glitch). The game required a chat/messaging feature, and not being able to find one to their satisfaction, Butterfield and co. built one from scratch.

As was the case with Game Neverending’s photo-sharing feature, Glitch’s chat feature soon became more impressive than the game itself.

And that’s how Slack was born.

Good Timing

Butterfield and his Slack co-founders Costello, Henderson, and Mourachov started working on Slack in 2012, which will forever be remembered as the year that A) the world didn’t end on December 21st, and B) people reached peak frustration levels with email.

2012 was the year we saw headlines like “Stop Email Overload” (Harvard Business Review) and “Be A Bitch On Email, Or Be Email’s Bitch” (TechCrunch). So it turned out to be a great time for Butterfield and co. to be working on a chat and collaboration tool that had the potential to make up for many of email’s shortcomings.

The fact that they were already well-known in the tech community from their Flickr days didn’t hurt Butterfield and his co-founders either. From the beginning, the product received tons of press that helped bolster Slack’s status as a tool that had the power to replace email.

Just look at some of these headlines from 2013:

- “Flickr Cofounders Launch Slack, An Email Killer” (Fast Company)

- “Flickr founder plans to kill company e-mails with Slack” (CNET)

- “The Co-Founder Of Flickr Wants To Replace Email At The Office” (Business Insider)

Again, the timing couldn’t be better: At the height of this anti-email fervor, a team with some serious tech street cred comes out with a product that promises to make company communication problems obsolete.

Slack’s genesis also coincided with another major event in the world of communication technology: Smartphone ownership reaching critical mass.

Between 2012 and 2013, the percent of adults in the U.S. who owned smartphones broke 50%, growing from 46% to 56%. The notion of being constantly connected — or, put another way, being unable to unplug — had become a norm, especially among tech-savvy business people.

Once again, this was good timing for Butterfield and co., who were A) developing a messaging application that was compatible with iPhones, iPads, and Android devices, and B) building a brand around improving inter-employee communication.

Want the latest & greatest growth strategies in your inbox? We write about that all the time. Click here to subscribe through our bot & receive our content regularly.

Slack Growth Strategy = Free Product + Loveable Brand

Slack is part of a recent wave of companies, which also includes MailChimp and Asana, that have adopted a product-driven approach to sales and marketing.

Instead of optimizing for MQLs (marketing-qualified leads) or SQLs (sales-qualified leads), these companies are optimizing for PQLs (product-qualified leads).

And all this really means is that instead of growing a massive database of contacts that needs to be combed through in order to identify people who could potentially be a good fit for the product, these product-first companies are focused on driving sign-ups. The name of the game is getting people to use the product as early as possible so they can experience for themselves how great it is.

Of course, part of that approach entails offering a completely free version of the product (payment, after all, is a pretty significant barrier to entry). Hence, any person and any team can use Slack for free … forever.

Pricing only kicks in if you want unlock more features, like additional storage or the ability to integrate with more apps.

But this freemium pricing model alone can’t account for how Slack has been able to drive so many sign-ups in such a short amount of time. Another big piece of the puzzle: the Slack brand.

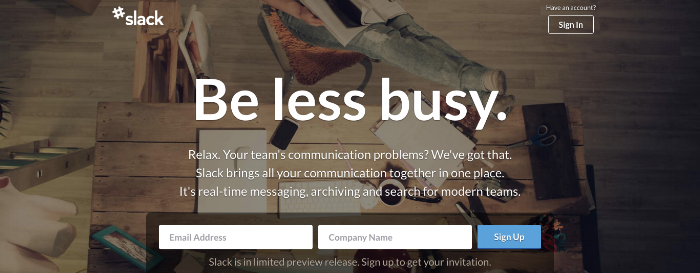

If we take a peek at what Slack’s homepage looked like back in 2013, it’s abundantly clear what action the company wanted you to take (“Sign Up”). But at the same time, their messaging was casual. Almost reassuring. “Relax. Your team’s communication problems? We’ve got that.”

And then there’s that full-width background photo of a desk with a bunch of crap on it … just like my desk!

That’s some good product marketing. It’s as if the founders of Slack understood what it’s like to work in an office, on a team. So instead of blasting us with jargon, they developed a brand voice that sounds like the voice of a trusted friend or colleague — someone who’s in the trenches with us, but who isn’t afraid to crack a joke and have some fun every now and then.

This playful-yet-helpful style carries over seamlessly into the product, where the colors, micro-copy, signature “knock knock” notification sound, and fun features like Slackbot all contribute to a cohesive (and lovable) brand experience. And perfecting that experience has been instrumental to Slack’s success.

As Butterfield wrote in a memo to the Slack team back in 2013:

“… even the best slogans, ads, landing pages, PR campaigns, etc., will fall down if they are not supported by the experience people have when they hit our site, when they sign up for an account, when they first begin using the product and when they start using it day in, day out.”

And to reiterate, Slack isn’t just focused on making their product stellar: All of the moving pieces that surround and lead into their product also need to be stellar.

As Butterfield noted, instead of getting people to understand their product’s value through sales and marketing, the Slack team was able to accomplish this “with copy accompanying signup forms, with fast-loading pages, with good welcome emails, with comprehensive and accurate search, with purposeful loading screens, and with thoughtfully implemented and well-functioning features of all kinds.”

Of course, that’s not to say that Slack has completely shunned more traditional approaches to driving awareness and growing sales. At the South by Southwest conference in 2016, Butterfield made it clear what his top two favorite marketing tactics are.

Number one: Word-of-mouth (no surprise there).

Number two: Paid advertising.

The thing that Butterfield likes specifically about paid advertising is that it’s easy to turn on and off. If an advertisement for Slack isn’t working, they can simply stop running it.

Compare that to what would happen if a massive sales operation you had built out stopped working …

As Butterfield said at South by Southwest:

“In a sales driven organization, it’s hard to rev up the speed because you have to hire more salespeople, and if you ever want to stop, you have to lay all those people off which is a horrible situation to be in.”

Final Thought

As far as sales is concerned, Butterfield was clear in his 2013 memo (titled: “We Don’t Sell Saddles Here”) that Slack isn’t in the business of selling messaging software. Instead, they’re focused on selling the innovation — the change — that their software can bring to teams and companies.

And at the broadest level, the innovation that Slack is selling is “organizational transformation,” which can manifest itself as “‘a reduction in the cost of communication’ or ‘zero effort knowledge management’ or ‘making better decisions, faster’ or ‘all your team communication, instantly searchable, available wherever you go’ or ‘75% less email.’”

Sure, this might all sound a bit aspirational. But when you consider how fast Slack has been growing, and how satisfied Slack’s customers are, it’s hard to claim that Butterfield’s strategy hasn’t been working.

Ultimately, however, Slack is a unique case. It’s product especially sort of lends itself to this PQL/SDR-less approach. Unlike most B2B products, Slack isn’t specific to one department or discipline. All teams need to communicate, which means once Slack gets into a company via individual users or teams, it has the potential to spread company-wide.

As a platform, Slack also has some unique advantages. As opposed to being a single tool that people use for a single task (re: chat), Slack can be used for a host of other communication and collaboration functions thanks to all the apps that integrate with it. What’s more, since these integrations are constantly bringing new functionality to the platform, Slack will continue to get more and more powerful — another big selling point.